Revisiting Marguerite Bourgeoys

The 400th anniversary of the birth of Marguerite Bourgeoys on April 17th affords us a wonderful opportunity, with the help of the archives, to revisit the contribution of one of this country's founders. Upon closer inspection, it is clear that her values remain firmly anchored in the collective consciousness and that her educational mission continues to this day.

Like Maisonneuve and Jeanne Mance, who preceded her by a decade, Marguerite Bourgeoys arrived in Ville-Marie in 1653 as a lay person inspired by the ideas of the France’ Great Century. The colony that welcomed her was very modest, but its inhabitants’ vision was ambitious and inspired by the Catholic Revival movement. That powerful movement proposed a social and religious life based on the principles of humanism, respect for others and self-improvement, all values that the first teacher in Montreal would use to establish a new society in the Americas.

Originally from Troyes in Champagne, it would only be at the age of twenty that Marguerite Bourgeoys decides upon the direction of her life. She chooses to live in the love of God, embodied in the love of neighbour, lived out in education. For her, as for others engaged in Catholic revival, religion could only make sense if it contributed to the well-being of the people. The educational model that she had in mind for girls, she wanted it for all children. As a result, the congregation of teachers she founded in New France would be comprised of uncloistered women who had the ability to move freely and go wherever their services were required.

A Forward-Thinking Teaching Manual

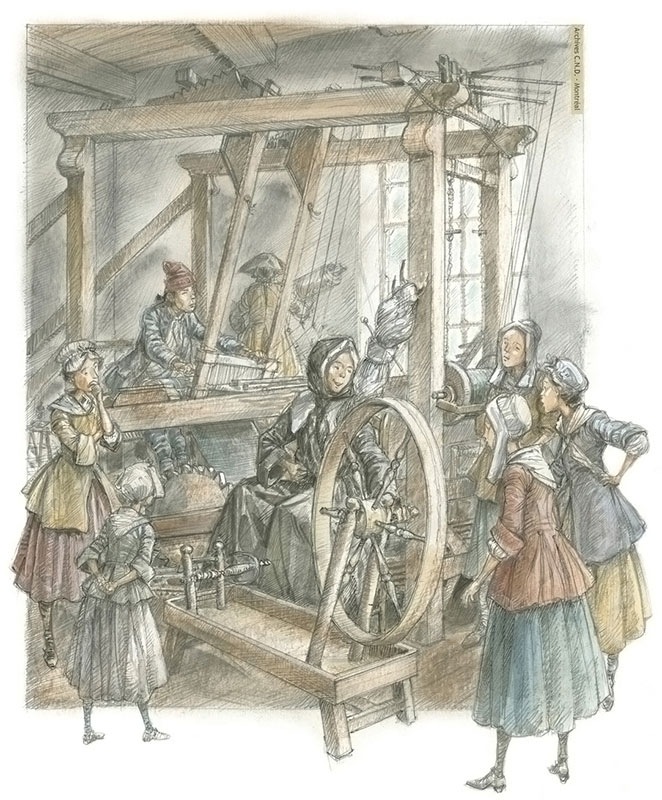

In her luggage, she brought a pedagogical textbook, written in 1640 by Father Pierre Fourier and in which he recorded the avant-garde practices of the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre Dame in Europe. These nuns, who ran schools for girls, moved beyond individual education to class-specific group education. Young girls learned not only reading, writing and arithmetic but also manual tasks. In Fourier's mind, thus educated they would be more attractive to prospective husbands.

This pedagogy was considered revolutionary in more ways than one. Primordial to this model is respect of the child. No longer considered as an adult in miniature; his or her uniqueness is recognized and is accorded the requisite time to learn at his or her pace. In this environment, corporal punishment has no place and one opt instead for stimulation and emulation. As for schoolteachers, they become teaching professionals; they will be among the first career women on the continent. At school, they form a faculty whose members collectively learn from one another. At all times, they are concerned about gaining the trust of parents to convince them of the value of education.

Enthusiastic Recognition by the State

Very quickly, Marguerite Bourgeoys and her first companions were very successful. Governor, intendant, bishop and Montrealers greatly appreciated their work, both educational and social, given that their home was not just a school. It welcomed orphans, abused women and children, the elderly and infirm. In Paris, their reputation is equally enviable. Louis XIV and his Minister Colbert are indebted to them for having taken care since 1663 of the King’s Wards sent to Montreal. When Marguerite Bourgeoys returned to France to have her group approved by the civil authorities, she is received with kindness and enthusiastically obtains in 1671 letters patent creating the Congrégation de Notre-Dame de Montréal.

This document is foundational in more ways than one. Firstly, it recognizes the principle of education for girls of European and Indigenous origin, free schooling, the establishment of a network of schools and the teaching profession. The king adds that he likes to see that these women are financially independent through the operation of their farm at Pointe Saint-Charles. The sisters were resolute in wanting to ensure their own financial autonomy as they did not want their work to be dependent on the whim of others.

Recognition by the Church won with great struggle

As the years went on, the number of schools increased along the St. Lawrence River reaching a significant part of the population. It would be the first school network in Canada yet they still did not have complete official recognition by the Church.

In the spring of 1694, the very conservative bishop of New France, Jean-Baptiste de Saint-Vallier, came to Montreal to visit the Congregation and present the sisters with a draft constitution which he described as a gift. He may have wanted to disguise his real intentions, but eventually showed his true colours. Elements contained in the text, such as solemn vows, the payment of a dowry, the creation of categories of sisters (choir sisters for teaching and converse sisters assigned to manual work) along with a special vow of obedience to the bishop, suggest the prelate's desire to eventually merge the sisters of the Congregation with the cloistered Ursulines of Québec City. In Montreal, they had always envisionned simple vows renewed every year. They rejected the notion of the dowry which would effectively close the door to girls from poorer families. Finally, they wanted all the sisters to be placed on an equal footing and not under the direct authority of a bishop.

Surprised by this document, a Trojan horse of sorts, the sisters showed their opposition by asking for time to reflect upon the content. Their interlocutor is furious that they would show signs of opposition. But fortunately, Bishop Saint-Vallier lacked time to submit them. He had to go back to France. This allowed Louis Tronson, superior of the Sulpicians in Paris and friend of the Congregation, to intervene on behalf of the sisters.

His efforts bore fruit. Saint-Vallier returned to Montreal in the summer of 1698 with a revised text. There were no longer any references to cloistered religious orders, the vows remained simple, and there was nothing about particular obedience to the bishop.

On the other hand, at the suggestion of Tronson, compromised had to be made. The revised regulations did not refer to the model of the Virgin Mary and other active women in the early Church, which the Congregation had so earnestly wanted. The division of the community into two groups was also maintained. The latter was a great disappointment for Marguerite Bourgeoys, who was convinced that a cook could become superior if she had the capacity and that, conversely, a superior could perform manual tasks at the end of her mandate. Finally, the dowry principle is maintained, but its application is relaxed.

Despite these concessions, the dream to create a congregation of uncloistered teachers is achieved. On June 24, 1698, 24 sisters in Montreal accept the new rule. The next day, in the presence of the bishop, the first public religious profession takes place at the Congrégation de Notre Dame.

Work inspired by a woman of action

Among Marguerite Bourgeoys' documents, her spiritual testament entitled The Writings is an exceptional piece of archival material. In 1697 and 1698, she recorded the reflections she wanted to pass on to those who would follow in her footsteps. These thoughts are both bold and modern.

In the chapter devoted to the Virgin Mary, which she symbolically refers to as the first superior of her Congregation, she paints a portrait of an active Christian, quite the opposite from the image of Mary as a passive and submissive woman. She says that from her youth, Mary became involved in her community as a teacher at the temple. On the death of Christ, abandoned by the apostles with the exception of John, Mary and other women are at the foot of the cross. Later, she writes, it was Mary who took the initiative at Pentecost to gather the apostles and launch the Church.

A little further on, she shows even more daring by comparing the sisters of the Congregation to the apostles. Nothing less! If these men could teach in the name of the Lord, she says, the daughters of the Congregation will teach school under the protection of the Blessed Virgin. And again, while the apostles went out to preach the gospel, the sisters of the Congregation must also teach it.

It took a lot of self-confidence to make such statements in the 17th century. But one thing is certain, she set the tone for decades and centuries to come; namely that women are called to assume their rightful place in both society and in the Church in the measure of their strengths and abilities.

It is this exemplary and legitimate ambition that Marguerite Bourgeoys leaves as a legacy and which still places her at the forefront of those who work both here and abroad to ensure equality between women and men, equal opportunities for all, mutual aid and mutual support. This valiant founder of the Congrégation de Notre Dame in the New World continues to define us!